I am partial to art and writing that encourage the viewer to become a participant—to engage with the work itself, and then to go out and make their own discoveries.

This month’s featured guest, Doug Wechsler, puts himself in the middle of the action of the natural world every day. He has traveled extensively—to Ecuador, Costa Rica, Borneo, and more—and through his images, books, and the stories of his experiences, Doug allows us to feel, to paraphrase one of his young readers, like we’re right there with the animals.

As I was putting the finishing touches on this newsletter, I heard the trill of a Screech Owl nearby. Dew seeped through my socks as I stood for a few minutes in the cold night air, under the light of a nearly full moon, listening to its whinnying call. Wherever you live, and whatever creatures are nearby, I hope you feel inspired to participate in the natural world around you.

Interview: Doug Wechsler

What sort of work do you do?

The focus of my work is to promote conservation by educating people about nature. As a writer, photographer, and naturalist, I communicate stories of the wonder of nature and how it works. My 25 photo-illustrated children’s books cover topics such as salt marsh ecology, how animals breathe, and the bizarre adaptations of insects. My long-time job with a museum, the Academy of Natural Sciences, took me to rain forests around the world. That work ultimately led me to four three-month stints as a volunteer host at biodiversity reserves in Ecuador. My wife, Debbie, who is an environmental educator, enthusiastically agreed to accompany me.

What aspect of your work has the most personal meaning for you?

Nothing pleases me more than hearing that one of my books has inspired a child to explore nature. It is my hope that reading my books will bring a better understanding and respect for the natural world.

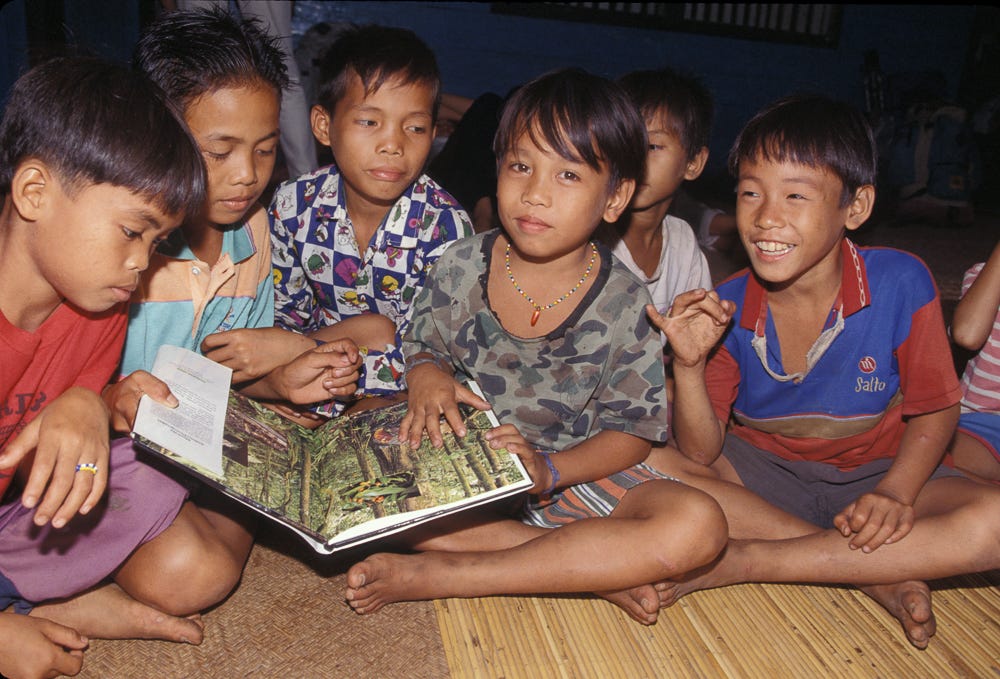

When I receive fan mail from young readers, it is heartwarming. Here’s one comment I received. “I like your books because it makes me feel like I am in the book just watching the frogs in there.” Kids don’t have to put on airs or adhere to convention, which means their letters are more revealing.

Even if I am well informed about the subject of my books before I start writing, I always learn so much more by researching the topic.

How are science, art, and writing part of your work, and how is the interaction between these areas important to you?

I use clear and engaging writing, along with aesthetically pleasing photography to explain scientific principles. I work hard to achieve artistic composition in photography that also gets the point across. The art of writing for children, in my mind, requires incorporating humor, word play, and literary devices, especially rhyme, metaphor, and alliteration. Blending these elements together leads to a successful and satisfying book that conveys scientific concepts and keeps the reader glued to the page.

Is there a particular scientific or environmental problem that feels important to you? What do you do about that?

The loss of rain forests, and more generally declining biodiversity, concerns me greatly.

As I mentioned earlier, I volunteered with an organization, the Jocotoco Conservation Foundation, at its reserves. Their eighteen reserves, though initially created to protect certain rare species of birds, in truth protect vital ecosystems in Ecuador.

We were privileged to stay where mist bathes the cloud forest and where the squawking of parrots is the background soundtrack. My role included educating tourists about birds, other wildlife, and types of forests and the important work of the foundation. I continue to support the organization financially and through social media and presentations about the amazing biodiversity that they protect and their many accomplishments.

How does your position affect your work?

As a naturalist, I endeavor to learn everything I can about the natural world and to immerse myself in it. This is both a source of inspiration and information for my books and my photography. It drives me to spend weeks in the field studying and photographing my subjects. Recently that included two three-week trips to Costa Rica and a trip to Panama. Over the course of my career, it has meant spending a total of 60 months in the tropics. I am observing nature every day and that drives my work.

What influences and inspires you?

I take my inspiration from bizarre parasitic wasps, huge trees, the cacophony of birds, and all the awesome players in the natural world. An experience in nature sparked each of my books. My first book, Bizarre Bugs, was inspired by the ‘weird-bug-of-the-day’ that I would bring back to our field camp in Costa Rica. Frequent canoe trips into salt marshes with my wife motivated me to write Marvels in the Muck: Life in the Salt Marshes. Participating in Toad Detour, an effort to save the lives of toads crossing a road in Philadelphia, led to my book The Hidden Life of a Toad.

The work of many great nonfiction authors influences my work, but I can point to two people who showed me it was possible. Watching photographer Michael Fogden in the field and seeing his work in print demonstrated to me that it was possible to make a living through nature photography. Similarly, observing my fellow wildlife biologist Ron Hirschi become a children’s book author convinced me I could do the same.

What’s your favorite method or technique to learn something new? (from Kate Rutter, 013)

Most of my books were only conceived after many hours of observing the subject in the wild. Direct observation is the best way for me to learn.

While writing my book The Hidden Life of a Toad, I realized I didn’t understand one of the basic elements of how a toad’s arms develop. I just assumed that arms start out on the side of the body as tiny nubs, which slowly lengthen and develop fingers. While photographing a toad tadpole one day with no arms yet, it swam momentarily behind a leaf and returned with an entire arm and hand! The arm had popped right through the skin. I realized that a toad’s arms fully develop underneath the skin then pop through quickly. So that’s how it works! Then I could finish the chapter.

Do you have a formative experience from growing up that you feel was your “spark” to lead to you where you are now? (From Jenn Houle, 006)

I don’t remember what the original spark was that started my life-long nature obsession. It certainly stems from having fields, woods, ponds, and streams to explore within walking distance of my childhood home.

Two influences in my childhood come to mind. The Wonders of Life on Earth by the editors of Life Magazine illustrated many iconic animals in their rain forest environment, all on one spread. I believe this may have sparked my desire to experience tropical forests. Years later in college, I got my first opportunity to visit the tropics. I was momentarily disappointed when I realized that seeing wildlife in the jungle was not as easy as the illustration suggested. I very quickly got over that notion, realized that hard work would be involved, and relished the experience.

Watching the television series Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom planted the idea in my head that I would like to catch animals in Africa when I grow up. I accomplished that once, when I was in Cameroon for a month doing field work that entailed catching birds.

Are you interested in collaborating with other groups or individuals on science-art-writing projects?

Working with others on nature-related projects would be fun, especially those involving photography. I would be most interested in those projects promoting conservation.

Thanks so much, Doug!

If you’d like to learn more about Doug and his work, please visit his website and follow him on Facebook.

This is wonderful Lisa. Seems like you and Doug have a lot in common in your approach and inspiration in the creative process.

Very neat! Thanks for sharing Doug's insights. Sometimes the best way to learn about something is to just observe for a while. You never know what you pick up on.