For a long time, I felt like I needed to choose between science, art, and writing. But when I let my work shift between these disciplines, it feels like noticing a star from the corner of my eye: I explore the blurry edges of my known world, and something exciting and beautiful inevitably comes into focus.

This month’s guest, Dr. Aaron M. Ellison, seems to have his eyes on those same stars. Over the course of his long career, across place and generations, he has engaged with with people, forests, carnivorous plants, climate change, ecology, photography, and more. These creative explorations have led him down productive and inspiring paths.

Interview: Dr. Aaron M. Ellison

What sort of work do you do?

I am an ecologist, photographer, sculptor, and writer. I study and creatively document the disintegration and reassembly of ecosystems following natural and anthropogenic disturbances; think about the relationship between the Dao and the Intermediate Disturbance Hypothesis; reflect on the critical and reactionary stance of Ecology relative to Modernism; and occasionally blog as The Unbalanced Ecologist. Over a 40-year career in science, I have written more than 300 articles, book chapters, and reviews of books and software; and written or edited 11 books. Since 2021, when I retired from Harvard, I have been the Executive Editor of Methods in Ecology and Evolution and, when not traveling or helping others improve their science, spend much of my time in my studio dedicated to woodworking, photography, and stained-glass work within the Artisans Asylum community workshop and maker space in Allston-Brighton, Massachusetts.

Now that you’ve stepped away from your work with Harvard Forest, what projects are you most excited about?

Since 2009, I have been working on the intellectual history of ecology and its relationship to Romanticism and Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. I’ve published two papers on one part of this topic—how ideas and perceptions of “landscape” contributed to the emergence and evolution of ecology as a scientific discipline and how they continue to constrain its intellectual boundaries—and I promised myself that this would be the first major research project I turned to after I retired. Indeed, in 2022, when I was a Natural Sciences Fellow at the Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study in Uppsala, I completed the first half of a book on this project, and hope to complete the book in the next year or two.

How are science, art, and writing part of your work, and how is the interaction between these areas important to you?

Science, art, and writing are all avenues through which anyone can express their own creativity. Although virtually no one would deny that art and writing are creative pursuits, artists, writers, and other creatives I have worked with often are astonished that “doing science” is also a creative act. Scientists observe the world around them, come upon unexpected phenomena, try to figure out why those phenomena occur and how to test those ideas, and then express their ideas and conclusions to others. The overall process is little different (and I would argue, not different at all) from the inspirations and actions that lead one to paint, sculpt, write, photograph, etc.

Could you tell me more about your own creative practice, and how your experience as a scientist is reflected in that?

As noted above, my artwork and my science are different aspects of my creative practice. My photography and woodworking reflect and are informed by my research on trees and forests. For example, my scientific understanding of how trees grow and how wood is produced contributes to techniques for working with wood, and for my constant goal to minimize/eliminate wood “waste” and use even the smallest scraps and splinters in new projects. Much of my photography centers on visualizing the dynamic nature of trees and forests.

In what ways have you seen scientists, artists, and writers benefit from collaborating?

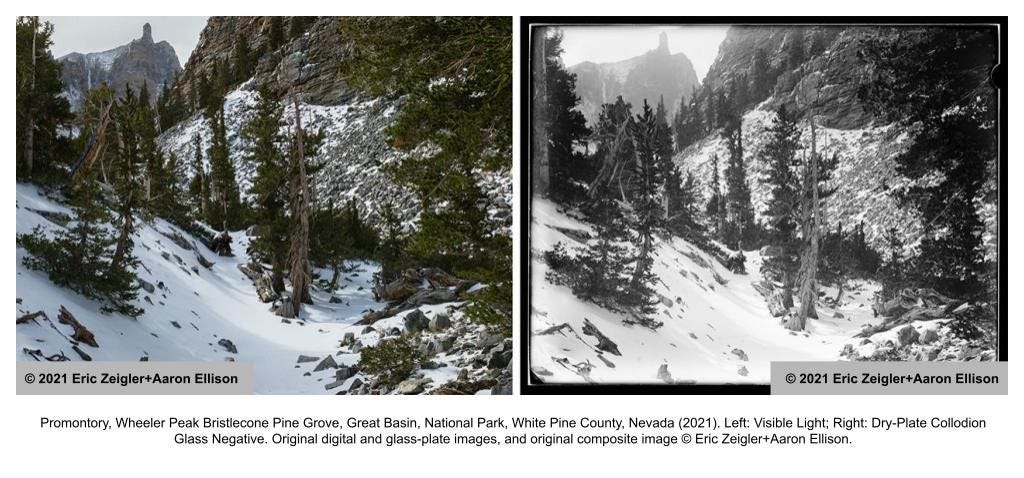

My best scientific work and my best artwork has been done in collaboration with others. All but one of my books and more than 95% of my published scientific work are the results of collaborations. I’ve a more even mix of solo and collaborative artwork; examples of the latter include three sculptural installations with David Buckley Borden (Hemlock Hospice, Warming Warning, and Novel Ecosystem Generator) and photography with Eric Zeigler (DoubleTake and Timelines). But even my “solo” work has benefited from informal collaborations with others.

Have you encountered resistance to this sort of collaboration?

Not really. But where I’ve encountered resistance or at least puzzlement is from individuals and committees responsible for judging artwork or selecting applicants for residencies. In my (albeit limited) experience, juried exhibitions, submission forms, etc. all assume a single artist is applying. There’s rarely a space for collaborators, never more than one contact address or email, and some exhibitions explicitly prohibit collaborative groups or teams from applying. This practice has long disappeared in the sciences, but the myth of the solitary artistic genius is hard to slay. David Buckley Borden and I published an essay in Leonardo about the “constructive friction” in art/science collaborations in which we also discussed some of the issues involved in communicating across the divide between C.P. Snow’s “two cultures.”

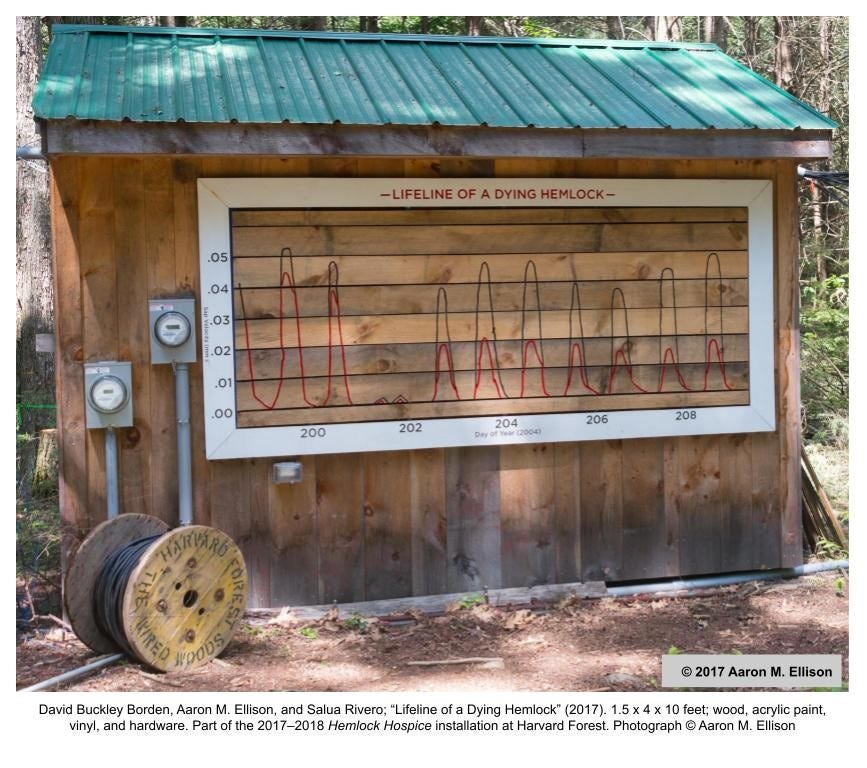

Have you ever worked with scientists to make art themselves?

The closest I’ve done here is in the Hemlock Hospice project. One of the pieces in that exhibition, “Lifeline of a Dying Hemlock,” was inspired by data collected by Prof. Nathan Phillips (Boston University) when my colleagues and I were setting up the Harvard Forest Hemlock Removal Experiment, a long-term experiment at the Harvard Forest aimed at understanding the effects of a nonnative insect (the hemlock woolly adelgid) on eastern North American forests. In 2004, we “girdled” more than 500 hemlock trees in about two hectares (20,000 square meters, or about five acres) of forest; girdling involves cutting through the bark and living conducting tissue to kill the tree standing in place (like the adelgid does). Nathan had put sensors to measure the flow of sap in some of the trees before they was girdled; as the tree was girdled, we could watch in real time (on a computer screen) the sapflow in the girdled trees fall by more than 50% (red line in the photograph below) relative to ungirdled trees (black line). To me, it was like watching a patient on an EKG start to die. I asked my colleagues if they felt anything about all the trees we were killing for this experiment (which, I must confess, I designed); they looked at me uncomprehendingly. I expressed my own grief over the “means” of this experiment in “Lifeline.” Any experimental scientist who doesn’t regularly ask themself if the means (methods) justifies the end products (knowledge, publications, etc.) isn’t being honest with themself.

What sorts of opportunities to increase diversity exist in this area? Are there concrete steps that people could take to be more welcoming and encouraging to people of different backgrounds and abilities?

I think that art/science collaborations present some of the best opportunities to increase diversity in both the sciences and the arts. Individuals from a range of backgrounds (genders, ethnicities, abilities, geographies, families…) all bring different perspectives to science and art, and when they can collaborate within and across disciplines, the results are simply amazing. In the 15 years (2004–2019) that I directed the Harvard Forest Summer Research Program, we supported incredibly diverse groups of students in the sciences, social sciences, humanities, and the arts (our work in this area was recognized with the 2014 Human Diversity Award from the Organization for Biological Field Stations).

The piece "Lifeline of a Dying Hemlock" (illustrated above) is one example of this sort of collaboration. It was co-designed and produced by me, David Buckley Borden, and undergraduate Salua Rivero. She had a background in both photography and biology, and put together a photography portfolio for her summer project.

How does your own identity and position affect your work?

I have been privileged to work as a professional, academic ecologist for nearly 40 years, teaching in private colleges and universities in New England (USA) and doing basic research and photography in the Americas, Australia, Europe, and Asia. My research has been generously supported by federal and state agencies in multiple countries and by private philanthropies, and has benefited from numerous collaborations with colleagues around the world. These positions, opportunities, and interactions are all reflected in how I think about ecology and its intellectual and social history, in my perspective on the relationships among ecology, the environment, and the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities, and in the art that I and others create together.

What influences and inspires you?

Long walks with trees and bioquantity (think: trillions of cicadas emerging in the Midwest in May.)

Where is your favorite place to get inspiration? (question from Wriley Hodge, 014)

Bristlecone groves in the Great Basin.

Anything else you’d like to mention?

For scientists, acknowledge your creativity and don’t be afraid to express it in many ways. For artists, acknowledge your collaborators and don’t be afraid to share the credit.

Thank you so much, Aaron!

You can learn more about Aaron’s work on his occasional blog and on the Harvard Forest website.

Truly fascinating read. As someone who believes in collaboration whether it be business, music, art, dance and not to add scientific study I found this article inspiring. I particularly liked Dr. Ellison's reference to the means getting to the result. The integrity and respect for nature and what it can teach us is truly humbling and necessary if we are to preserve and ultimately enhance the earth.