Breaking Down Barriers

Featuring: Maia Buschman

I am happy to welcome Maia Buschman to Twig & Ink this month! The combination of Maia’s interest in both film and ecological grief (or eco-grief) first caught my attention, but as often happens, I discover so much more—about the person, the subject matter, and the creative process—through these interviews and the conversations that happen behind the scenes.

The concept of eco-grief refers to the complex feelings of sadness and loss related to the destruction of the natural world, often, but not exclusively, when this destruction has human origins. The first time I realized there was a name for this feeling was when I saw the installation piece Solastalgia, by Sophy Tuttle. Like Maia’s video, it faces a challenging subject with both bravery and nuance.

I hope you enjoy learning about Maia’s work as much as I have.

Interview: Maia Buschman

What sort of work do you do, and how does it relate to the intersection of science, art, and writing?

I currently work full-time with the Aldo Leopold Foundation, whose mission is to foster the land ethic through the legacy of Aldo Leopold. Leopold himself was a big advocate for breaking down the barriers between science and art; throughout his life, he used drawing and writing to explore the world around him and gather data. His book, A Sand County Almanac, has done so much to show how artistic expression can advance science—it’s his lyrical and poetic writing that pulls readers in, and it continues to speak to people today.

I also help out part-time with the Wormfarm Institute, a non-profit that works to integrate culture and agriculture and uses art to showcase rural values, lifestyles, and futures. Every other year, they host a really cool event called Farm/Art DTour, where artists are commissioned to create large-scale pieces that are integrated with and speak to the rural landscapes of Wisconsin; people can go on a driving tour in the early fall to experience all the artworks, as well as local markets, food vendors, and more.

And what about your work outside of those organizations?

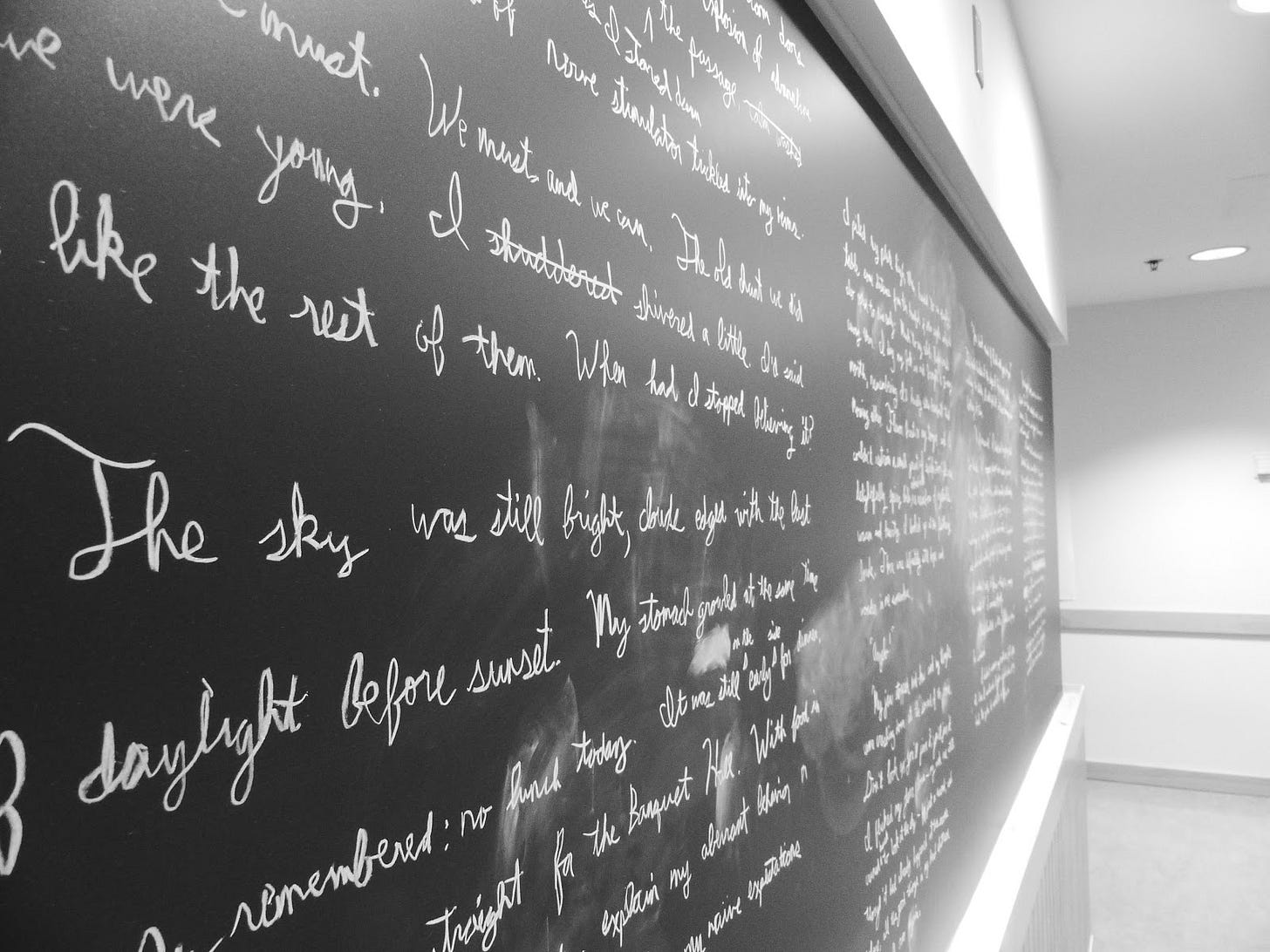

I am, at heart, a writer, and have been pretty much my whole life. I especially love writing fiction stories and novel-length projects, but over the years I’ve also gotten into other genres, such as essays and screenplays.

My other great love is photography, and much the same as writing, it’s been a years-long process of trial and error, exploration, and experimentation. I started a photo blog back in early high school and did a photo-a-day practice for six years—the commitment to the hobby has stuck, and I usually have a camera on me whenever I go anywhere new!

How does the interaction between science, art, and writing play out in your projects?

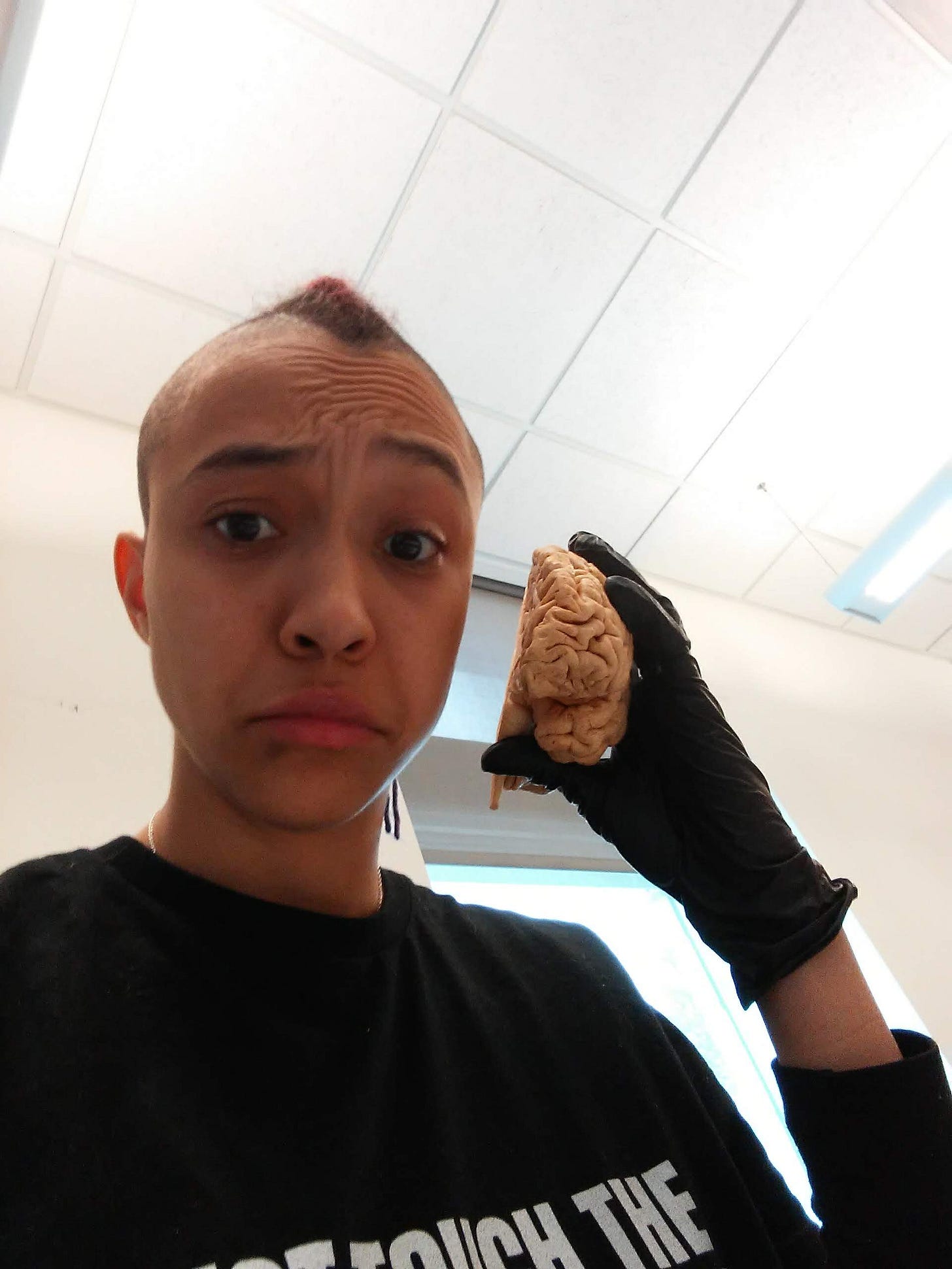

I’m eternally curious and love learning about and geeking out over science-y things, and then showcasing that learning in odd or wacky ways. Some notable past examples include (in middle school) filming a video that explained the greenhouse effect and global warming using Cup Noodles, or (in college) writing a parody/cover song that identified the function of different areas and structures in the brain. For me, absorbing knowledge through different media such as videos and music was a saving grace during school, and helps me stay curious beyond academia.

It was definitely this same impulse that steered me toward video essays. I wanted to go beyond the written essay and make it more engaging and accessible to different audiences. My first video essays were created in place of final papers in college, and a way to bring together something I loved with the themes of the class: for example, analyzing the nature ethics of Yusuf/Cat Stevens’ music before and after he converted to Islam. Expanding into multimedia allowed me to incorporate the source material as it was intended to be consumed. (I especially wanted to include snippets of the songs in question!). With my recent project, Never to Revisit, I wanted to showcase historical photos and nature imagery, and include interviews as well, so going the video essay route made the most sense to tell the full story.

It sounds like Never to Revisit brought a lot of your interests together. What are some of the underlying themes it helped you explore?

I created Never to Revisit as an investigation of human connections to wild places. I was really drawn by the seeming contradiction within Aldo Leopold's "Green Lagoons" essay: the celebration of wilderness juxtaposed with lament at what's happened to it. Realizing I'd felt echoes of that, seeing beloved natural places under threat, I wanted to expand my analysis to include other voices beyond Leopold's—other degrees of wilderness beyond his definition. What is this environmental grief we're experiencing, what can we learn from it, and what can we do for the wildness we love?

I'd definitely be interested in exploring these themes more in the future, and bringing conservation psychology into my environmental work going forward.

Quick detour, because conservation psychology is new to me. Could you tell me more about it?

Conservation psychology looks at human behaviors, attitudes, and emotions around the environment. The ultimate goal is to understand environmental issues through the lens of human behavior and cognition, and to figure out how best to shape human action to be more sustainable. For example, how can we disrupt habitual patterns of transportation like driving in single-occupancy vehicles; or how can we frame political messaging around climate change to appeal to the differing value structures of liberals and conservatives? I sort of came to the field by accident, which is to say I took an intro psych course and an intro environmental studies course and wondered how I might be able to combine the two.

Do you have a memorable experience that has solidified your belief in the value of the work that you do? (from Shirlene Chiam, 012)

I was lucky to be able to host a virtual program premiering Never to Revisit, and the feedback I received was so deeply heartening. So many people wanted to share their own experiences, the wild landscapes they cared about and the change they had witnessed over time; and so many people were inspired to discuss the themes with loved ones afterward. I truly feel humbled that this little community was so willing to engage with my project and explore these ideas. The process of making the final product was very internal and solo a lot of the time (thinking, analyzing, reading, researching, writing, revising, speaking on camera, gathering media, editing the video), and even when I told people about it, it didn’t feel real because I didn’t have much to show for my work. But seeing folks’ responses to the final product and opening up that dialogue was very moving, and showed me that all that internal/solo work is valuable and can still have a meaningful an impact on others.

In addition to what you’ve already talked about, are there other environmental problems that feel important to you? What do you do about those concerns?

Coming from a conservation psychology background, the biggest problem that I see with regards to the environment is apathy. I’ve been fortunate enough to study and work in little “bubbles” of folks who care deeply about environmental issues, but the fact of the matter is, once I step outside of the bubble, “the environment” is a niche concern. I think the greatest way to combat that is to tap into values, observe what people do care about. There are so many in-roads and ways to get people involved, and it almost always starts with the emotional component and the values. There’s so much going on in the world today, and in people’s individual lives, and cognitive load and compassion fatigue make it even more difficult, so starting with what people already do care about and invest in and finding the tie-in lowers the barrier to entry.

What sort of mental or social barriers have you encountered when advocating for the relationship between art and science? How did you overcome them? (From Derek Russell, 002)

I’ve been fortunate so far in that most people are open to the creative crossovers, but certainly some folks think they exist separately—I think the art/science “dichotomy” is closely tied to the emotion/reason “dichotomy,” and that bringing in imagination, sensation, feeling, and experience as a way to tell stories about the facts or data is sometimes seen as “unprofessional.” The way I see it, emotion exists to convey reason, to give it depth and dimension and personal relevance, and it feels the same with art and science.

Are you interested in collaborating on science-art-writing projects?

I am definitely interested in collaboration! I really enjoyed getting to reach out to and work with the interviewees I chose for Never to Revisit, and in the past, I’ve teamed up with friends and classmates on other film projects.

As I worked on Never to Revisit, I started to wonder who else was connected to the “wild place” I loved, and how I might find these others and create a community around our shared love and belonging. While I cannot pursue that particular path right now (mostly because I’m physically somewhere else), I am still and always eager to make connections with others who love their little pockets of nature, and would be excited to share that love through some kind of art. Right now, a friend and I are working on a photo series of a nearby marshland as we revisit it every season, and exploring how our own sense of place changes through the year and the more times we go back.

Is there a particular way of working that feels integral to your work?

The ability to be experimental is so important for me. The freedom to try new things and go in weird directions, whether or not they work well or have the expected outcome, has always been part of my creative process. And taking multiple things that are important to me and finding ways they integrate and intersect makes the process that much more fun! Not only do I get to unite my different interests, but I end up learning and expanding my own worldview as well. And in addition to that, taking note of what others are doing, too, and getting inspired by them. I’m a consumer just as much as—if not more than—a creator.

If you could live your life over again, would you do anything differently? (from Dr. Aaron M. Ellison, 018)

I really wish I could go back and assert myself more—not let things slide, proclaim my feelings. But as painful as it is to look back on those times I failed, I realize that this is a long and ongoing journey for me, and I’m trying my best to be compassionate to myself as I learn and grow and gain that confidence.

Thank you, Maia!

You can learn more about Maia’s work on her blog and YouTube channel. And be sure to watch her video essay Never to Revisit!