Twig & Ink has been around for long enough now that previous guests have exciting new updates. I love to be reminded that amazing people and incredible work don’t just happen; both grow out of hard work, and develop over time. I look forward to sharing more updates on Twig & Ink guests in the future!

This month, please enjoy new work from Marina Schnell. You can learn more about her path to this point by reading her previous Twig & Ink interview.

Welcome back, Marina! Could you tell us about your new project?

Every senior at College of the Atlantic is tasked with designing a senior project, and I chose to create an illustrated field guide to intertidal invertebrates and algae. Here’s an excerpt from the introduction:

“In the most basic sense, the intertidal zone is the area of shoreline that is covered by water at high tide and exposed at low tide…. The organisms that live here withstand the most difficult aspects of both terrestrial and marine life: crashing waves, fluctuations in temperature, desiccation by the sun, inundation by saltwater, predation. Their adaptations to these conditions are widely varied, from shells to scales to spines, air bladders and toxins and cells that can lose nearly all their moisture before rehydrating with the tide.”

The in-between nature of the intertidal is so compelling to me, and I was excited about the prospect of spending more time with the creatures who live there.

I’d love to hear more about your inspiration for the field guide!

Before my first marine biology class at COA, I didn’t know (or care) much about anything that lived in the intertidal. Four years later, I’m elbow-deep in it. But I remember what it’s like to know nothing, and I think that helps me guide other people who are new to it.

Starting out, I was overwhelmed by detailed keys without illustrations, and frustrated by guides that were so simplified that they were incorrect. I wanted to create an in-between.

What felt particularly important to communicate in your guide?

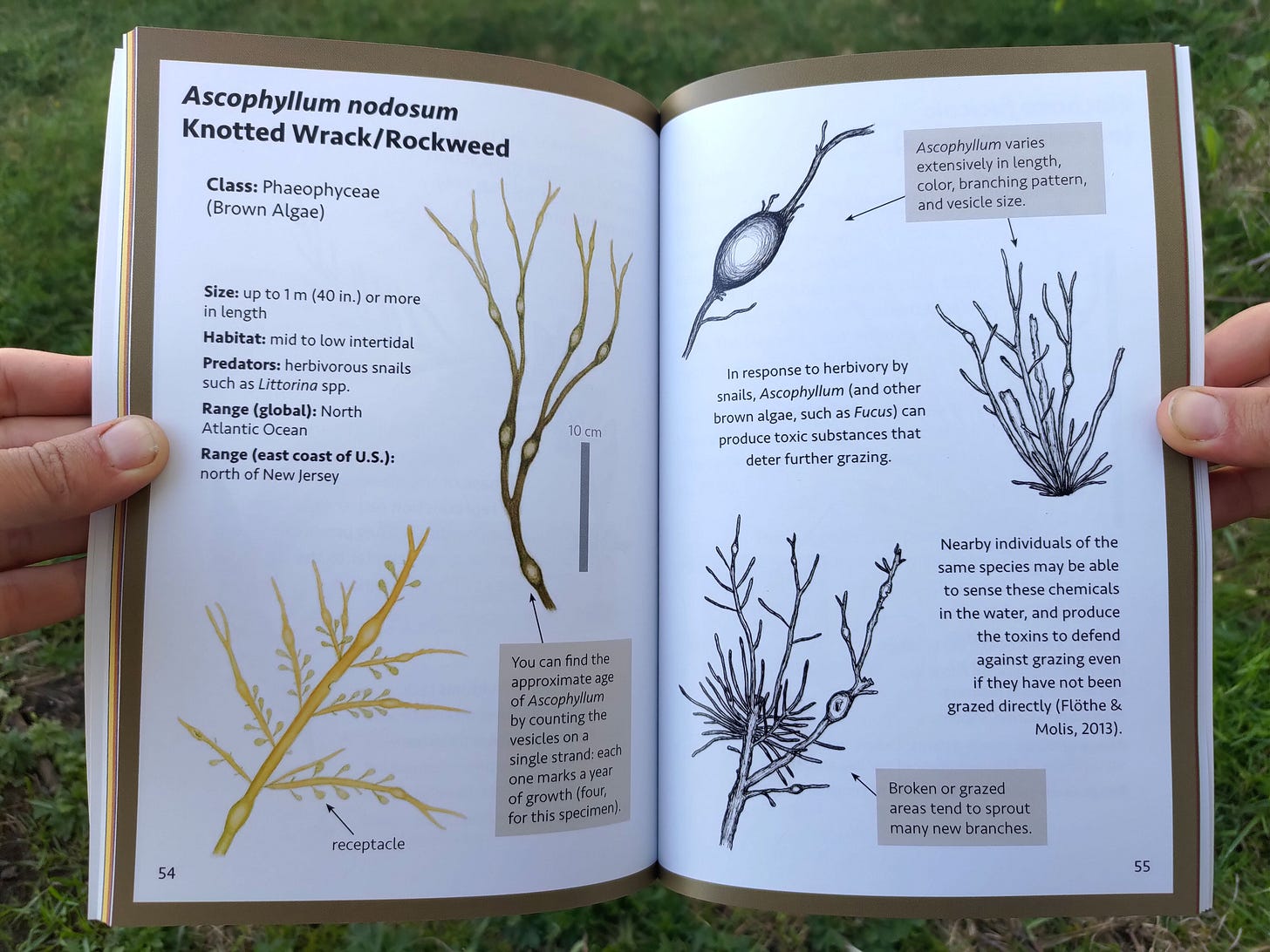

Identification in the intertidal is challenging because the same species can look quite different in different environments. For example, the common seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum (see sample spread) might be dark olive green or bright yellow, and the air bladders might be tiny or massive or absent. Intense waves can affect the way these organisms grow, as can predation or herbivory, or the chemical composition of the water. In this guide, I wanted to make people aware that this variation is possible.

Also, this project pushed my verbal and visual communication skills in unexpected ways, as I shifted from field sketching to scientific illustration, and from academic writing to a broader audience. The goal this time was to help other people see.

How do illustration and other forms of art affect your relationship to science?

For me, illustration is a valuable way to understand the creatures I study, as it forces me to pay full attention to their anatomy and other characteristics. At what angle does a snail’s shell coil? What happens where the leg meets the body of a crab? What color is that seaweed, really? It goes both ways—observation makes me a better illustrator, and illustration makes me a better observer.

And, as a friend once put it, “doing art makes me enjoy the science I do more.” Sometimes blending art and science is the answer, and other times I just need to take a break from one by spending some time with the other. Returning to a project with fresh eyes (and a fresh brain) can jolt me out of a rut.

How did you decide which species to include in your guide?

These species are the subjects of an annual intertidal survey conducted at 11 field stations throughout the Gulf of Maine (the Northeastern Coastal Stations Alliance, or NeCSA). Long-term monitoring is essential to understand changes in any ecosystem, and because this survey is standardized, researchers from these different field stations can compare their results.

I’m hardly the first person to say this, but I think that in environmental crises (climate change, endangered species, etc.), the problem is often not a lack of information, but a lack of effective communication. This survey, and the collaboration involved in its creation, is an exciting effort to better understand our local intertidal and the ways it may be changing. The next step is to communicate this to people outside the circle of those who already know and care.

This guide is partly an effort to bridge that gap. I hope it will be useful to the variety of people who do the survey, from high school students to experienced researchers, as well as anyone who just wants to explore the intertidal. Maybe it’ll even reach someone who didn’t think they were interested.

What else inspires your work?

I read Pilgrim at Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard for the first time recently, and this passage from the essay “Seeing” particularly struck me:

“I used to be able to see flying insects in the air. I’d look ahead and see, not the row of hemlocks across the road, but the air in front of it. My eyes would focus along that column of air, picking out flying insects. But I lost interest, I guess, for I dropped the habit. Now I can see birds. Probably some people can look at the grass at their feet and discover all the crawling creatures. I would like to know grasses and sedges—and care. Then my least journey into the world would be a field trip, a series of happy recognitions.” (p. 15)

I’ve never been drawn to nonfiction when I read in my free time, but I loved Annie Dillard’s writing. The way she braids different storylines and approaches everything with both gravity and a subtle sense of humor is—honestly, it’s awe-inspiring.

How have your interactions with the intertidal affected you personally?

The intertidal was an anchoring point for me in the strange new world of college far away from home. I learned to resolve the greenish-brownish expanse into familiar species of seaweed, and to get on my knees and lift the fronds to find snails and crabs and hydroids beneath.

Once, I went out to the intertidal with someone who stopped at a tide pool I’d long since dismissed as uninteresting. We found a massive nudibranch (sea slug) there! Shaggy, pink, and nearly two inches long.

These creatures seem to me so obviously fascinating that sometimes it’s hard to comprehend that not everyone feels that way. Seaweed that becomes poisonous when snails nibble on it? Anemone larvae that merge with their siblings? Parasitic castrators? I couldn’t make this stuff up. I don’t know how to persuade someone that these creatures are worthy of attention. All I can do is say “look! look!!! isn’t this crazy? isn’t it beautiful?”

Thank you, Marina!

You can learn more about Marina and her work here and also from her previous Twig & Ink post. Marina’s new book, The Water’s Edge: A Field Guide to Rocky Intertidal Life in the Gulf of Maine is available here.

I loved reading this, and proud of the work you both are doing!

Wonderful collaboration between you two, & art, science, literature, & the fascinating world of nature.